Thinking

Brands as acts of leadership

We use cookies to help you navigate efficiently and perform certain functions. You will find detailed information about all cookies under each consent category below.

The cookies that are categorized as "Necessary" are stored on your browser as they are essential for enabling the basic functionalities of the site. ...

Necessary cookies are required to enable the basic features of this site, such as providing secure log-in or adjusting your consent preferences. These cookies do not store any personally identifiable data.

Functional cookies help perform certain functionalities like sharing the content of the website on social media platforms, collecting feedback, and other third-party features.

Analytical cookies are used to understand how visitors interact with the website. These cookies help provide information on metrics such as the number of visitors, bounce rate, traffic source, etc.

Performance cookies are used to understand and analyze the key performance indexes of the website which helps in delivering a better user experience for the visitors.

Advertisement cookies are used to provide visitors with customized advertisements based on the pages you visited previously and to analyze the effectiveness of the ad campaigns.

Brands as acts of leadership

For the first time, Impressionists were not representing subjects, but rather focusing on human experiences.

Change in culture rarely happens in sudden leaps, but there are exceptions. Every so often, single dates make everything different.

On April 15th, 1874, a former photography studio in Boulevard des Capucines, Paris, premiered the works of a movement called the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, Printmakers, Etc. The paintings – on sale during the show – depicted contemporary life in a technique that looked rough and unfinished to both art critics and the general public.

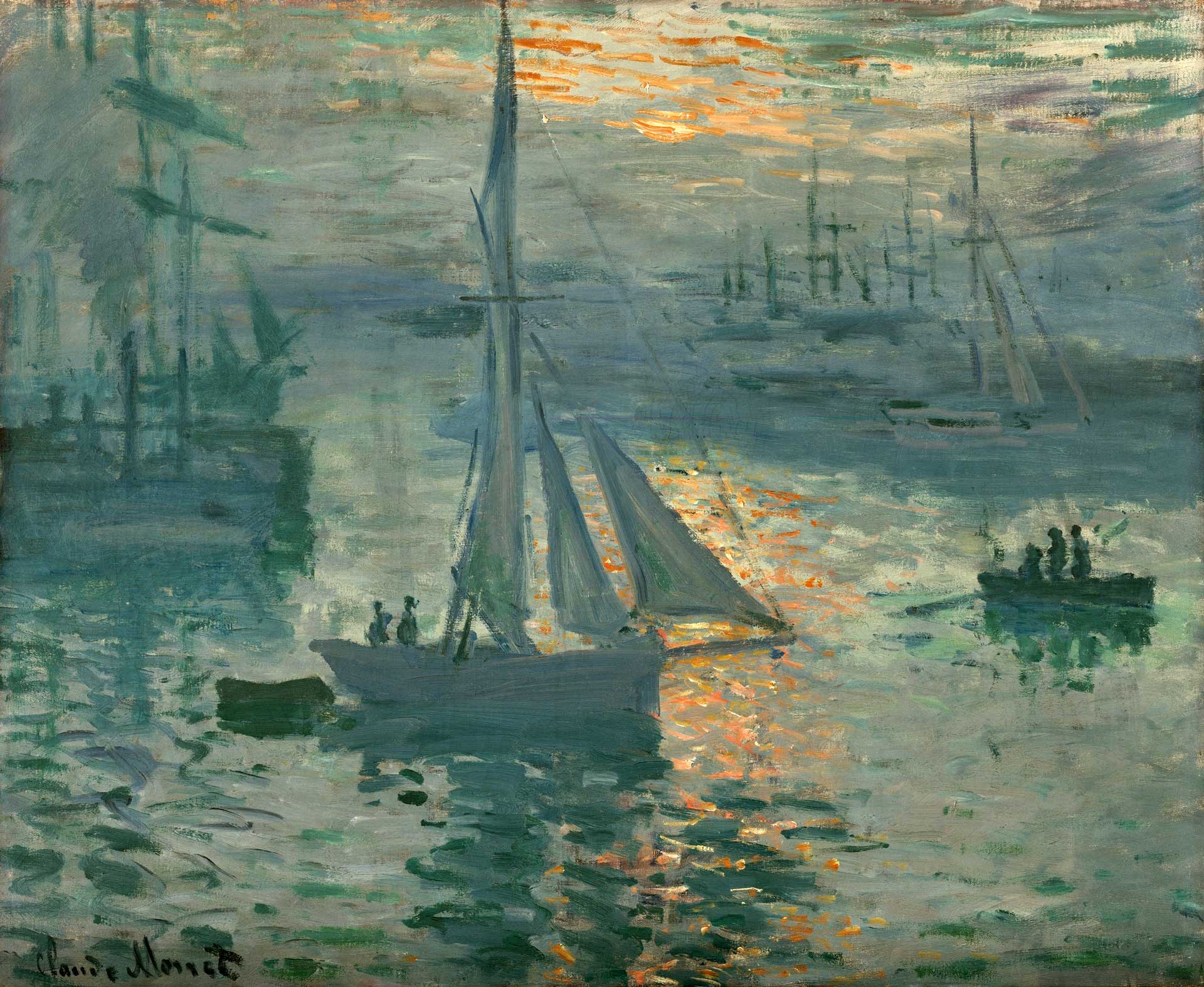

The exhibition was far from successful. Beyond incurring a significant loss, it attracted insulting criticism and derision. Louis Leroy, a critic, sought to discredit the artists by mockingly dubbing them after one of Claude Monet’s paintings: “Impression: Sunrise”.

Today, that premiere is remembered as the first Impressionist exhibition – and the date marking the beginning of modern art. In much of the world, visual art was never to be quite the same again.

Showing boldness and facing huge controversy, artists like Monet, Paul Cézanne and Alfred Sisley made a radical departure from the conventions of art – and, by extension, their society. They did away with secular dogmas, institutions and traditions. In so doing, they deliberately threw the gates open to experimentation, giving their contemporaries newfound freedom to experiment in a manner previously unseen – ultimately paving the way to influential new styles and much of the art we see today.

But what was the change really about? For the first time, Impressionists were not representing reality, but rather focusing on its human experience. They were capturing fleeting moments – impressions, as it were – with bold, hurried strokes rather than pursuing academic realism through obsessive refinement. They were celebrating a more intimate connection between individuals and nature, and assimilating faraway cultures.

Most importantly, they were abruptly rejecting traditional canons and embracing modernity – changing their way of working to reflect the world they lived in.

The Impressionists’ boldness to make a conscious departure from conventions, swim against the tide and put new ideas above much easier careers didn’t only create some of the most iconic artworks in history. It drew a line in the sand, igniting a change that would reverberate for generations to come, expanding the possibilities of art and expression.

—

It is hard not to be inspired by the bravery and significance of the Impressionist revolution, its power as a movement to challenge conventions and create immediate change, as we look at both the context and the brands in our 2021 Best Global Brands study.

On the one hand, there’s the context.

It’s not looking good, and can be best described as a roomful of elephants. Climate change. Inequality. Resource depletion. Overconsumption. Humanitarian crises. The world is still not working very well. And yet, brands are. They continue to be powerful constructs that drive beliefs, behaviours and choices, and connect billions of people to some of the world’s most influential organisations, unlocking an aggregate value of over $ 2.6 trillion.

And so we are, as brand leaders, at an inflection point.

And so we are, as brand leaders, at an inflection point.

We can sit back, and accept brands as an inevitable part of the problem – engines for consumption with unavoidable consequences. We can cling on to the traditional consumerist paradigm, and continue to manage brands purely as assets that provide value to customers and shareholders, with the broader and longer term consequences as the price to pay.

Alternatively, we can be inspired by the moves of some of the brands in this study, and look at brands as part of the solution. We can dare to reimagine them as the connective tissue between business and society, investors and people, profit and purpose, leaders and constituents, present consumption and future resources.

In 1874, the Impressionists chose to break away from traditions, and rethink the very essence and purpose of art in a changing world.

Today, as brand leaders, we can choose to preserve the inertia of corporate branding dogmas – or we can leap ahead, rethink the very function of brands in this decade – and reengineer their role in societies.

—

The most critical social and environmental debates of our times share a common denominator – the future of individuals, societies and our planet. They focus on the will to endow the next generations with undiminished – or, ideally, even greater – possibilities.

Some of the rising brands in our study are actively expanding possibilities, by driving decisive innovation, developing kinder, more viable business models, making hard choices and taking uncompromising stances.

These brands lead from a better future. They engage people and foster their participation, making them part of a movement. Ultimately, they become more than simply relevant – they are seen as part of the solution, not the problem. Their growth becomes a matter of common interest.

Conversely, some organisations are failing to tangibly and quickly adapt. These will increasingly be seen as being part of the problem, not the solution. Their growth will be questioned as producing future costs and sacrifices – ultimate limiting possibilities.

Defining an inspiring, credible and authentic purpose may be complex – but it isn’t hard. What is hard is actually serving it.

The 1920s saw the development of the idea of externalities – the consequences of production or consumption unwillingly sustained by third parties.

One century later, externalities have abandoned the realm of economic theory. They are no longer distant or invisible issues – they are clear and present, and are increasingly central to any organisation’s legitimacy to exist, operate and grow.

Growing public awareness and information means that any brand’s externalities will undergo the same level of scrutiny traditionally reserved to its core products, services and experiences. Increasingly, the question facing any business leader – and their brands – will be whether they are part of the problem or the solution; expanding or limiting our possibilities.

What side are they on?

—

Notions such as stakeholder capitalism and purpose are not new, and are now mostly accepted. The issue now is walking the talk.

Defining an inspiring, credible and authentic purpose may be complex – but it isn’t hard. What is hard is actually serving it.

A considerable part of the problem between talk and walk is the old paradigm of going at it alone.

The ticking time bombs of this decade are too large for any single organisation or individual in isolation to address them in isolation. The simple truth is that universal, systemic problems require widespread, systemic collaboration. And this is where brands come in.

Brands influence our individual beliefs, belonging and behaviours. But what strong brands do is unite people and create movements around shared goals, principles and a desired future.

As the shape of capitalism changes, the role of brands in this decade will not be to ‘change the world’ – but, rather, to give their constituents the agency, means, connections and conviction to do so; to be collaboration platforms – helping creators, consumers and communities collaborate and adhere to shared principles.

By making changes in individual behaviour desirable – after all, that’s what brands are great at – brands can connect their customers to their wider constituents, managing their externalities as part of their business.

—

Of course, this is easy to say, but harder to serve. What does this mean, in practice, for the way leaders build and manage their brands?

Our Best Global Brands study reveals a compelling chain.

In order to influence behaviours beyond sheer consumption, brands must be relevant, along three dimensions – presence, trust and affinity.

They must be present – part of the conversations that are important to their audiences and their ethos; they must create affinity by playing a meaningful role in customers’ and constituents’ lives by taking clear stances on the principles and priorities that are key to them; and they must engender trust – the confidence that a brand will not just deliver on a promise, but behave with their constituents’ interests in mind.

But how do you create relevance?

Our data shows a distinct correlation between the Best Global Brands’ relevance and the degree to which they engage constituents – through moves that are distinctive, coherent, and that invite participation.

In turn, what are the necessary condition for creating engaging experiences and moves?

Again, our data provides valuable insight. Brands that are able to engage their audiences are those that show exceptional leadership – a clear direction, full alignment, empathy and understanding of constituents, and agility.

Leadership →

DIRECTION

DIRECTION

ALIGNMENT

ALIGNMENT

EMPATHY

EMPATHY

AGILITY

AGILITY

Engagement →

DISTINCTIVENESS

DISTINCTIVENESS

COHERENCE

COHERENCE

PARTICIPATION

PARTICIPATION

Relevance

PRESENCE

PRESENCE

TRUST

TRUST

AFFINITY

AFFINITY

Let’s rewind: our data shows that the world’s most influential brands activate a clear chain: Leadership creates Engagement. Engagement creates Relevance.

Where does this take us? At a time of crisis of confidence and trust in institutions, government and society overall, we must rethink brands as acts of leadership.

Businesses that want to be relevant must fill in the void. They must be seen as leaders at the forefront of a transformation that transcends their categories, sectors and traditional approach in order to take advantage of the opportunity of what our postpandemic world can be like.

Brands that are thriving at the beginning of this decade lead from the future, engaging people in a journey towards that future, and giving us the choice and agency to act according to shared principles.

So as brands set out to expand our present and future possibilities, here are five priorities for brand leaders.

First, see profit as a resource.

At a time of income insecurity and rising collective concerns, priorities and needs are being reassessed. In high-consumption societies, frugality will be embraced. Growth as an end in itself is being challenged. So, determine clearly what your business’s role in the world might credibly be, and then define how its profit and growth can be seen as a valuable resource enabling your constituents to drive real change.

Second, pick your battle.

No single business can effectively lead the charge on more than a single systemic issue. So be sharp, focused and authentic when defining what your role in the world and contribution can truthfully be. Be crisp and clear on what your societal enemy is, and what you can realistically do about it.

Third, think arenas, not sectors.

It will be increasingly hard to build strong communities around products and services; much easier to do so around fundamental needs – like move, play, connect and express. Categories and technologies come and go; needs stay and evolve. Define the arenas you are actually competing in.

Fourth, be accountable.

Have your purpose as your north star, but be clear on your ambition – i.e., what you’re setting out to tangibly achieve in the next couple of years. What is the best version of your organisation at a given date, and how are you actually going to measure it?

Lastly, make moves, not campaigns.

This decade’s challenges need less visions and communications, and more action and delivery. Your brand manifests itself into much more than your customer journey – it is, in fact the way your business exists as a human experience for all your constituents. Rebuilding a fairer supply chain to is no less part of the experience than, say, your channels.

At a time when slow, gradual evolution is not just good enough, as brand leaders, we badly need an Impressionist moment. We need that same courage to face controversy, challenge deeply entrenched dogmas, accelerate change and rethink the very nature of what we do.

Just like the Impressionists abruptly reimagined the function of art in a changing world, we must rethink the role of brands for the decisive times we live in. Like them, we must place human experience, rather than tired conventions, at the centre. Like them, we must expand possibilities for those to come.

There has never been a better time to think bigger and together. To make brands not just assets – but, most importantly, acts of leadership for these decisive times: a decade of crucial challenges, yes – but also immense possibility.