Why invest in branding?

In this second installment of a fascinating foray into the fundamentals of branding, Calin Hertioga and Johannes Christensen explore why you should invest in branding, and how it creates economic value.

Say you’re the Chief Executive Officer at a big company and want to convince the board of directors to invest $100 million in production capacity. You will probably get asked what the return on investment would be, so you prepare in advance. Based on past projects and benchmarks, combined with other available information, your team calculates potential revenue, subtracts production cost and projects it over time to estimate how much money you expect to make with the new capacity (and when). The business case is soon ready for you to present.

Right before the board meeting, the Chief Marketing Officer comes with the proposal to invest another $100 million in branding. Not marketing, branding. You look at him in silence for a few seconds, contemplate firing him, then dismiss him with a tentative laugh. For now. Who comes up with such a joke? You need serious people in your organization.

You would be right, and wrong. You need people that are as serious about branding as they are about production. Your CMO may not have been wrong to ask for the money, but he was wrong to not bring the business case along.

Or maybe he was wrong about the money too? Leading the branding effort shouldn’t be his job, it should be yours. Branding should be a CEO’s job, because it influences every dollar that production capacity will deliver in the future. Without good branding, those estimations may be over-optimistic at the least.

But how much should you invest in branding, and what does it bring? To get towards an answer let’s look at the mechanics of how branding creates value.

Atoms of economic value: transactions

Whether your organization sells smartphones, fitness programs or jet engines– anything really – the principles of value creation are the same. Buyers pay you money in exchange of future benefits from using the products and services you are selling.

To create economic value[i] over time, you want buyers to buy from you (and not competitors) repeatedly, preferably at a price enabling a nice profit margin.

For this to happen, they need to recognize you, trust you and like you. As it happens, branding is one of the most effective tools for sellers to influence buyer recognition, trust and affinity – and thereby generate economic value.

Recognition

Imagine your friend – let’s call him Uncertain John – wants to buy a cell phone. He finds a list of specifications from different unidentified providers and they all sound similar. On his way to work, he sees cell phone advertisements on the subway, but cannot distinguish the manufacturer. At work, his colleagues rave about the different new phones they bought – without mentioning the names of the phones. After work he walks into a store to buy a phone. But which one? John can’t link the information he has assimilated with the individual offers on display. There was no explicit (or even implicit) association with a specific phone company in all the touch points he had. His choice thus becomes dependent on what happens in the store, and if all the products seem equal, his choice will be random.

This is a fictitious example but think about all the advertisements you’ve seen in the last week. How many do you remember, and what companies were they? The less the seller is recognized along the customer journey, the more the risk increases for the buyer to buy from someone else, especially if the offers are similar. As a seller, you want to be recognized at every touch point. Easier said than done.

Recognition comes easily in one-on-one relationships and in small communities. Humans are biologically wired to recognize other humans, by their faces[ii], body shapes, movements and sounds. This process works less well for animals and objects. Primeval “branders” decided to facilitate recognition of their property – Old Norse cattle owners “brandr-ed” their cows, ancient Chinese potters signed their ceramics, emperors stamped coins with their faces and created uniforms for their troops. Fast forward to today, there are countless more touch points by which entities can be recognized, yet the way our brains work hasn’t changed much at all[iii]. Just as we recognize faces by certain simplified traits, we look for information shortcuts to recognize entities behind products and services.

Early branders only needed a symbol to stick to their products. If you want to do good branding today, a visual symbol (say, a logo) will likely not be enough. Branding is everything you do with the intention of being recognized[iv]. Would a swoosh do? What about painting everything red? Spreading the same perfume in the stores, always using a playful tone of voice, a familiar, jaunty jingle – or all of the above?

In order to determine what signals to send to which buyers with which touch points, to optimize the way you help them with orientation in the marketplace, you need a brand strategy.

Recognition alone is not enough though, and if your brand strategy only deals with sensorial elements, you’re not addressing the whole process of getting to a transaction. Buyers can recognize multiple sellers promising them all kinds of benefits – but whom do they choose? And why?

Trust

In a world of perfect information, buyers could transparently quantify the benefits of each phone, gym membership or jet engine on offer. Their choice would be clear – buy from the seller offering the highest benefits. But we don’t live in such a world. In our world, buyers get partial, imperfect information about all offers. There is also a time gap to bridge before any transaction can happen. When a professional buyer is looking to purchase a jet engine, she cannot guarantee that it will work for the next 20 years, as needed. She believes it will, and she believes that the company will be there 15 years down the line to help service it.

The buyer must make a leap of faith at the moment of every transaction. The following three inputs are feeding it:

1) Observation and interpretation of signals

This includes (but isn’t limited to) the way the jet engine seller interacts with the buyer, the manners, education and knowledge of their salespeople, the content and design quality of promotional material, things noticed at the factory visit, the way the engine looks, press articles, specialist forum ratings, color, tone of voice, specs. All these touch points send signals that the buyer’s brain interprets (decodes[v]) and compares, leading to them favoring a certain seller.

2) Previous experiences of promises made and kept

Non-first-time buyers of jet engines can draw upon past events and remember what various sellers promised and kept – or haven’t kept[vi]. Everything you say and do can be used by the customer in their future purchase decisions, for or against you.

3) Reassurance from other buyers

One of the core characteristics that distinguish humans from animals is believed to be the notion of cumulative culture[vii] – we can believe stories from and about people whom we’ve never met. This enables knowledge transfer for all members of the species who ever get in contact, rather than for just the members of one family or tribe. Today’s technology helps us expand this input to the entire connected world. The offers you are deciding between may have ratings from people all over the world. Some references count more than others (especially for things like jet engines), but the principle remains – buyers base their judgment not only on their own experience, but on the experience of everyone they know or have heard from.

These inputs and their influence on purchase vary by industry and type of transaction. For first-time or one-time purchases – a new fitness subscription you want people to try out, or souvenirs in a tourist shop (where buyers are not expected to return) – observation and decoding of signals may be enough to build enough trust to trigger a transaction. If your business is built on serving a constant stream of new customers, branding for sensory and short-term memory[viii] can help you attract more. Recognition may not be as important in these cases. An entirely generic tourist souvenir shop placed at the perfect spot next to a tourist attraction can be successful without a name, logo, visual identity or any other elements to distinguish it from other souvenir shops elsewhere.

If your business relies on returning customers, you want to find an anchor in buyers’ working and long-term memory. You want buyers to know it was you who sent the right signals, to remember it was you who delivered on promises previous times, you want them to talk about you to other prospects. For that, they need to recognize you.

Thus recognition – the primary objective of branding – serves to bind experiences into buyers’ long-term memory and, if the experiences are positive, build trust towards sellers. As a seller, you should invest in knowledge, skills and capabilities necessary to create, orchestrate and produce touch points that send trust-building messages to the buyers. Branding will help you bind these messages to your entity (rather than competitors), ensuring that trust is built over time.

And still, recognition and trust are often not enough. A buyer can recognize and trust that more than one seller delivers on needs. Rolls-Royce and GE can be trusted to deliver good jet engines, Samsung and Apple can be trusted to deliver good mobile phones. Runkeeper and Runtastic can be trusted to deliver a good fitness service. But how does one choose? Buyers can flip a coin – or choose the option they like more.

Functional benefits – “Your products and services solve a problem or provide opportunities”

Emotional benefits – “I share values with this organization and feel good for supporting it”

Social benefits – “Buying this says something about me, expresses my values and personality for others to see, enabling me to belong to a certain tribe”

As a consumer, professional buyer, supplier, or job seeker, I trust that Apple and Samsung, Siemens and GE, Runtastic and Runkeeper (the list goes on) to deliver products and services of a similar quality. Yet I am equally likely to develop a preference based on affinity. Am I an “Apple person” or an “Android person”? What does buying from Siemens say about me, vs. buying from GE? Am I Runtastic or a Runkeeper? For some of these associations I may also be willing to pay more – or less.

The higher the affinity the buyer has for a certain seller, the higher the chances for repeat transactions, and for higher price premiums to be obtained.

Branding as a management tool

Based on every interaction they have with you, buyers will build an image and a narrative[x] about you in their minds, which will influence their desire to buy or not buy from you. If they recognize, trust and like you, if they believe what you believe, if your offer helps them express themselves, they will be more likely to buy.

In a start-up, founders and their small teams design most of the company’s touch points together or in close alignment, which makes it easier to influence the stories in buyer’s minds. As soon as the number of people in an organization exceeds 150, the limits of effective personal collaboration tend to be breached[xi]. Beyond the size of a human “tribe” (where everyone knows each other and can hold each other accountable for the common good), guidelines are needed to regulate any collaboration.

In large organizations, touch points are created and managed by many individuals in different functions, each with their own agendas, skills and moods. If you leave buyer experience at the discretion of your individual employees without guidance, good luck creating a coherent image and narrative in buyer minds. Alternatively, you can try to influence employee behavior and thus buyer experience with a clever brand strategy.

A good brand strategy should be anchored in understanding human recognition and its influence on trust and affinity. It should ideally include inputs from psychology, sociology, biology, anthropology, statistics, language, literature (and more). It should comprise a target narrative you want buyers to build and tell about you, an image you want to project and self-expressive benefits you want to provide, along with guidance and examples on what consequences these should have in practice. A good brand strategy needs a comprehensive set of skills and resources. Its implementation requires a consistent organizational effort. It also needs conscious and targeted investment.

Investing in branding

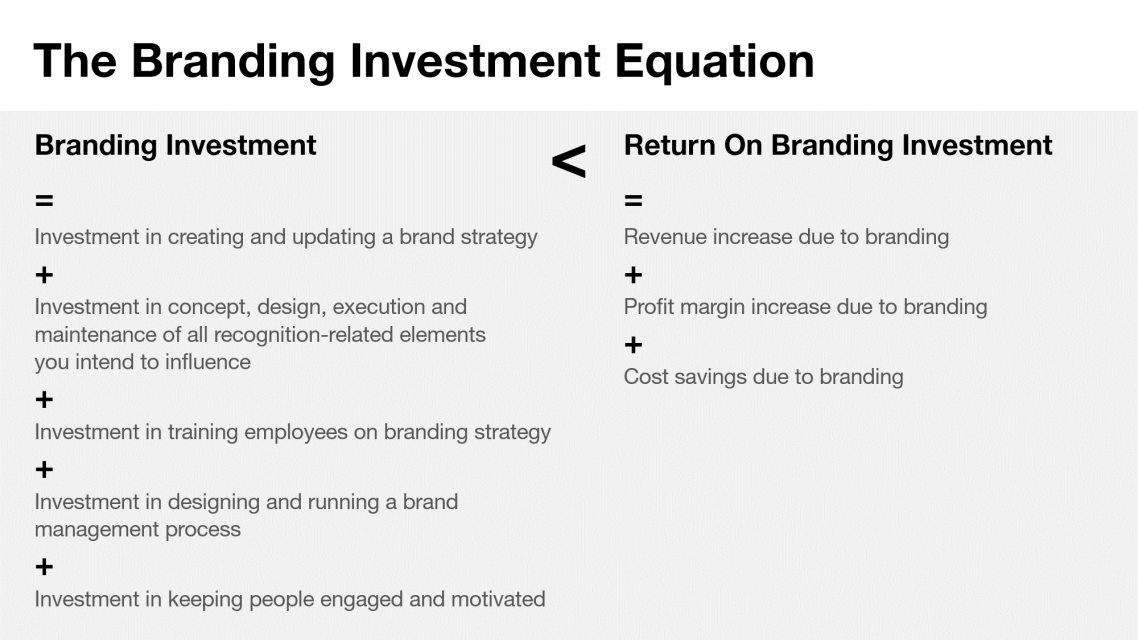

Branding is everything you do with the intention to be recognized, and recognition binds trust and affinity. Therefore, to estimate investment requirements for a good brand strategy, one would have to:

- Identify all touch points the seller can influence for buyer recognition

- Assess their impact on purchase – e.g. through market research – and prioritize

- Estimate the cost to create and implement the brand strategy, including:- Brand strategy creation cost – for own team, potentially with consultant aid- Internal training on brand strategy for all employees (functions to prioritize could be strategy, product development, design, marketing, sales, human resources and customer service)- Impact test for “branded” experiences on purchase– via market research or prototyping exercises

At first read, it seems to be a simple equation, however its elements aren’t easy to quantify. This stacks the cards up against branding professionals. If they have a hard time calculating the return on investment for their advice, their remuneration must be based on hourly rates – which makes the investment in creating even a most sophisticated and original brand strategy low compared to what benefits it can create if implemented well. But this is advantageous for companies who see the opportunity to invest in a good brand strategy and execution.

The more your product developers and service designers understand both their buyers’ behavior as well as your own brand strategy and address them in their work, the more efficient and effective your organization will operate, and the less testing investment will be required to calibrate (and the less Uncertain Johns you’ll encounter). Everyone in business – and life – does some branding but not everyone does it well. What makes a brand strategy and execution good? That’s for a follow-up conversation.

References

Below a list of references, for your information, entertainment, or outrage.

[i] Economic value = the value of an asset calculated according to its ability to produce income in the future: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/economic-value

[ii] https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/how-does-your-brain-recognize-faces-180963583/

[iii] Harari, Noah Yuval – Sapiens

[iv] https://interbrand.com/views/what-is-a-brand/

[v] Read: Decoded, by Phil Barden, or Codes, by Philipp Scheier, if you prefer the German language

[vi] https://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/24/your-money/why-people-remember-negative-events-more-than-positive-ones.html

[vii] https://www.lse.ac.uk/philosophy/blog/2016/03/03/what-makes-humans-special/

[viii] More on memory types: sensory, short-term, working, long-term: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-psychology/chapter/types-of-memory/

[ix] Maslow’s needs are not necessarily a pyramid: https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2012/03/29/what-maslow-missed/#cfc0f07661b5

[x] Humans have always had to deal with multiple information inputs into their decision making – now more than ever – and have developed a simplifying strategy to cope with all of it: storytelling. We are storytelling animals: everything we observe we automatically fit into a narrative pattern humming in our brains continuously. The implication is that once you are recognized repeatedly along multiple touch points, before you know it you will be associated with certain characteristics.

[xi] On Dunbar’s number: https://qz.com/846530/something-weird-happens-to-companies-when-they-hit-150-people/